Quakers stand up for vital legal precedent established in 1670 Quaker trial

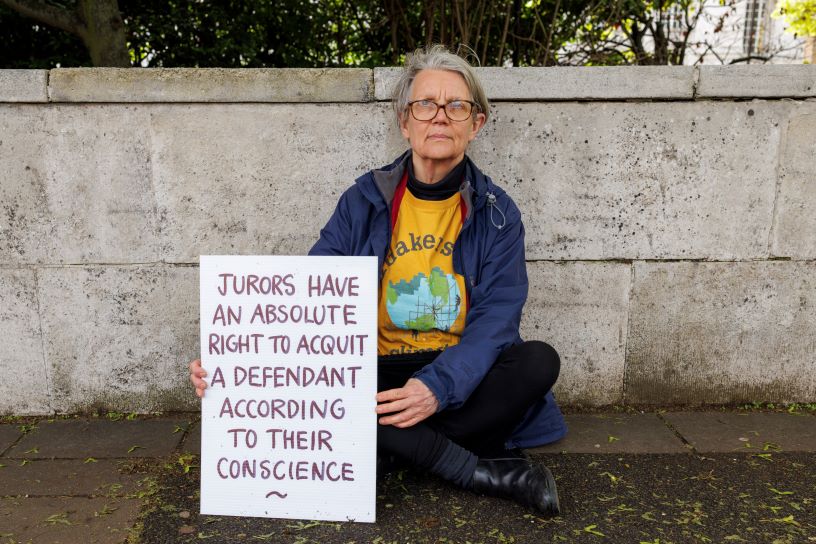

Twenty-four ordinary people have successfully protested outside a court to remind jurors of their right to make decisions according to their conscience.

Quakers Rajan Naidu, 72, of Birmingham, Phil Laurie, 56, of Faversham, Fran Wilde of Selly Oak, and Joanna Hindley, 57, a midwife from Birmingham, are among those who held signs around Inner London Crown Court.

These read: “Jurors have an absolute right to acquit a defendant according to their conscience."

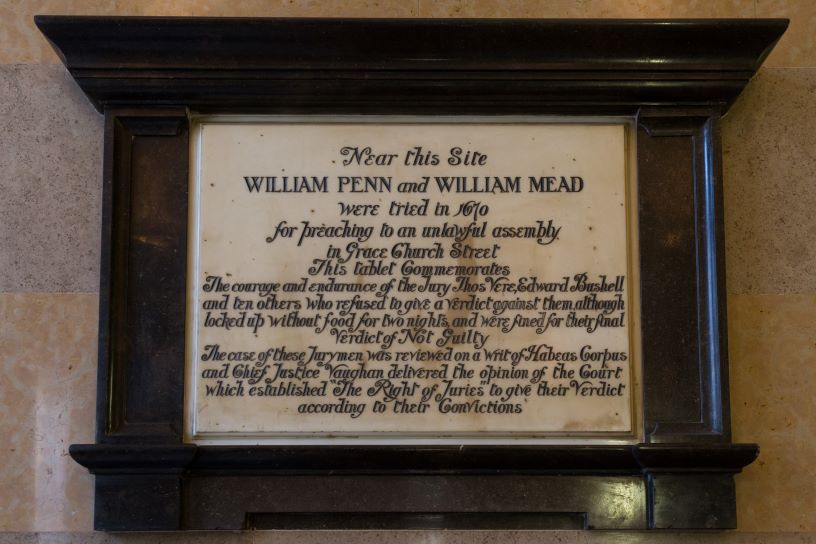

This right, first established in 1670 when the Recorder of London tried to compel a jury to convict two Quaker preachers, William Penn and William Mead, for holding an unlawful assembly, has been challenged recently.

Judge Silas Reid has banned defendants in nonviolent civil disobedience cases from mentioning the rights of jurors, or the words 'climate change' or 'fuel poverty'.

This appears to be a response to some judges and juries acquitting defendants in nonviolent civil resistance cases when they have explained their motivations in court.

Judge Reid previously ordered the arrests of four people displaying the same message nearby, accusing them of attempting to influence the jury.

This week, as Judge Reid heard another Insulate Britain case inside, seven medics, a former police officer, a former lawyer, two teachers and others offered a show of solidarity to the defendants.

But in a climb-down, the court ignored the protestors, thus undermining any possibility of prosecuting those previously arrested.

The legality of Judge Reid's ban on defendants discussing their motives is uncertain, and of particular resonance to Quakers.

One judge, Mr Justice Cavanagh, has stated: “It is not the case in any trial that jurors can acquit by their conscience if by that it is meant that they can disregard the evidence and directions given by the judge and decide on their own beliefs whether a defendant is guilty of a criminal offence."

But as children are taught in British schools, this has not been the case since 1670 when Penn and Mead were arrested for holding a Quaker meeting in Gracechurch Street, London.

During the trial, jurors refused to find the two men guilty of speaking to an unlawful assembly, despite the jurors themselves being fined and locked up by a judge without food or water for two nights.

Later the Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, Sir John Vaughan, ruled that a jury could not be punished on account of the verdict returned.

Since then, juries have been free to arrive at decisions independently, without fear of punishment. This right is recorded on a marble plaque at the original entrance to the Old Bailey.

Photo credit: Paul Clarke on flickr

This independence, protestors said in a letter to Judge Reid, safeguards religious minorities, like Quakers, and “provides for a jury to reject any prosecution which they perceive to be politically motivated, an abuse of power or contrary to basic morality."

“...when jurors are denied the opportunity to hear why defendants have taken their actions, they are also denied the opportunity to exercise their moral common sense, contrary to natural justice, the right to a fair trial and the ancient principle established by Penn and Mead," the authors wrote.