8 things you may not know about the right to vote

Jessica Metheringham highlights eight lesser known facts about the struggle for the right to vote in Britain.

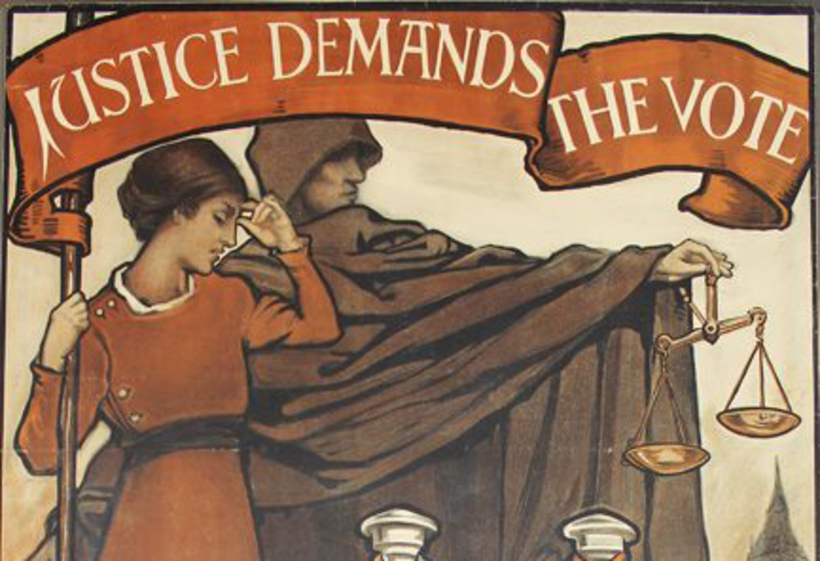

Today, 6 February 2018, marks 100 years since the Representation of the People Act was granted Royal Assent and became law. It was a landmark piece of legislation. For the first time, women were explicitly included in the franchise for national elections. Many Quakers were involved in long-standing universal suffrage movements including Anne Knight, Alice Clark, Emily Ford, Hilda Clark, Helen Sturge and Edith Pye.

However, 1918 wasn't the only important date in the struggle for votes – and it's certainly not the first time that women voted. Here are eight things you may not know about the right to vote.

1. Before 1832, some women could theoretically vote in national elections.

The Reform Act of 1832, which standardised voting across the country, explicitly banned women from voting. Before that, individual counties and boroughs elected national representatives in different ways, and because many franchises were based on wealth and property, female landowners would have been entitled to a vote. Because the property of married women was held by their husbands, this usually meant wealthy widows. A woman like Catherine de Bourgh from Pride and Prejudice (published 1813) would have probably have been entitled to a vote, although she may not have used it, or she may have sent a male proxy to vote on her behalf.

2. Landowning women could vote in local council elections until 1835

Local council elections were restricted to men by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835. The right to vote in local elections was restored to women in the Municipal Franchise Act in 1869, giving a local government vote to single women who lived in a property which paid property tax. In 1894 this was extended to married women. They were still required to live in a house which paid property tax, which meant that voting for councillors and mayors was limited to wealthy women.

3. The Representation of the People Act 1918 did not include all women

The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave women the explicit right to vote in a national election. This was a hugely significant change, recognising that women should have a say in who runs the country. But it wasn't all women – only women over the age of 30, and only if they were on the Local Government Register, married to someone who was on the local government register, or a graduate voting in a university constituency.

4. Conscientious objectors were excluded from the right to vote

There were approximately 16,000 conscientious objectors during World War I, Quakers amongst them. Under the terms of the Representation of the People Act 1918, conscientious objectors were excluded from the right to vote for the duration of the war and for five years after it ended.

5. Equal votes for women and men was introduced in 1928

Women didn't get the vote on the same basis as men until the Equal Franchise Act 1928, ten years after the Representation of the People Act. The minimum voting age was 21. It dropped to 18 in 1969.

6. Women couldn't sit in the House of Lords until 1963

Women could be elected to the House of Commons from 1918 onwards, but it wasn't until 1963 that women were allowed to sit in the House of Lords. The first female peers had actually been announced in 1958, so legislation was slow in allowing them to take their seats. Margaret Haig Thomas, the Viscountess Rhondda, had spent her life campaigning to be allowed to take her hereditary seat. She died in 1958, less than a month before the first female peers were announced.

7. Until 1948 university graduates could vote more than once

Until 1948 some people could vote more than once in national elections. Graduates of some universities could vote in a non-geographical university constituency. This vote was in addition to the constituency in which the person lived – so someone who had graduated from Oxford (for example) got to vote twice. These university alumni constituencies were abolished in 1948.

8. You can still be registered (and vote) in more than one place

People who live in two different places can still be registered to vote in each place, but can only vote in both if they are voting in different elections. Someone who lives in Dorset at the weekend and in London during the week could vote for both Purbeck Council and Haringey Council, because these are separate councils covering separate geographical areas. However, that same person can't vote twice in a general election, because a national election covers both Dorset and London.

The history of the electoral franchise in the UK is a history of discrimination, on the grounds of wealth, education, and sex. While our electoral system has come a long way since 1832, it is still poorly understood and in need of care. The centenary of the Representation of the People Act is a time to speak up for the political system we want to see, one which allows all voices to be heard, which is transparent and fair, and works for the common good.