A matter of conscience: Quakers and conscription

Conscientious objection

Men could claim exemption from military service by applying to a local tribunal for a certificate of exemption. There were four grounds for exemption:

- if employed in, or being trained for, work of national importance

- if one's dependants would suffer serious hardship

- ill health or a disability

- a conscientious objection to the undertaking of combatant service.

An estimated 16,000 men registered as conscientious objectors (COs), 10,000 of whom were engaged in some form of alternative service while 6,000 were arrested and imprisoned. Most COs fell into one of two groups: alternativists or absolutists.

Alternativists are often contrasted with absolutists. However, the difference was probably on a spectrum rather than a case of two distinct groups. Many conscientious objectors changed their position, in one direction or the other, during the war.

Absolutists

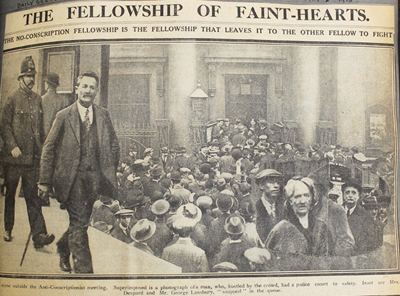

Absolutists were unwilling to perform any kind of service that might help the war effort. They comprised mainly members of the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR), the Independent Labour Party, and socialist groups.

Many Quakers joined the NCF, formed by Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway. It was Britain's leading anti-conscription organisation and supported those who resisted the Military Service Act. Absolutists challenged the government's enforcement of the act, which included the procedures in local and central tribunals, military courts, and civilian prisons.

Alternativists

Alternativists sought an alternative to military service. Quakers found roles for themselves in many different ways. Some men and women accepted other work as long as it was not under military control. Examples included offering religious provision or helping charities collect unwanted clothes.

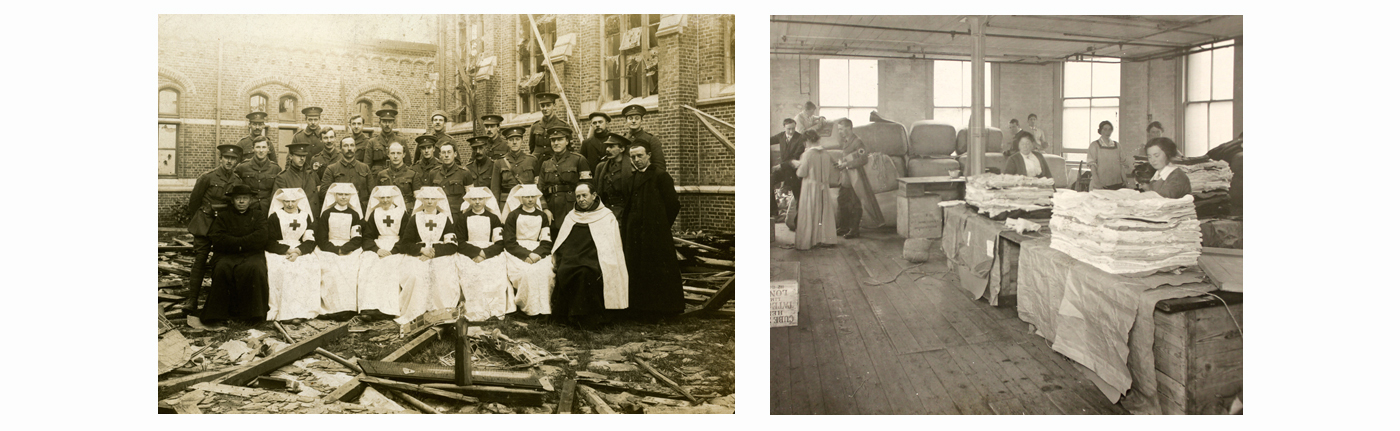

Many Quaker men accepted non-combatant service, joining the military but not bearing arms, for example in the Non-Combatant Corps or the Royal Army Medical Corps. This was the main option for Quakers who felt they could not take a passive stance. Despite their opposition to war, many wanted to stand beside their fellow man at the front and to share his experiences. By 1916, as the Military Service Act was being enforced, the number of volunteers to the NCF and the FoR had rocketed.

Some people objected to the concept of conscription itself, so while the Quaker Corder Catchpool joined the Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU) of his own accord in 1914, he left the unit in 1916 in protest at conscription and was sentenced to prison.

Many Quakers joined the Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU) or the Friends War Victims Relief Committee (FWVRC) as a form of alternative service. The FAU was set up in August 1914 by Philip Noel-Baker, who later became a Labour MP. Independent of the Society, it oversaw the training, deployment and support of unenlisted volunteers from all faiths to tend to wounded soldiers and civilians in France and Belgium.

The FWVRC, an official committee of London Yearly Meeting, worked to relieve the suffering of civilians caught up in the war. It offered the French government the voluntary services of doctors, nurses and others to provide whatever help was needed. This included building shelters, staffing maternity hospitals, and helping with agriculture and supply lines of food and clothing.

To find out more about the choices made by Quakers in World War I, read our

White feather diaries (site no longer in existence).